Hamstring Strain

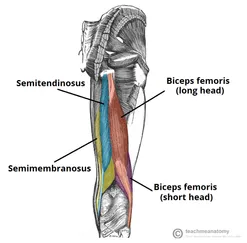

The hamstring muscle group contains 3 muscles: the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris. The muscle group is partly in charge of hip extension and mostly in charge of knee flexion (bending the knee). These muscles may be strained from excessive stress during contraction or from extreme stretch. Strains most commonly involve the biceps femoris near the back of the knee (1,2).

How do you grade a hamstring strain?

Hamstring strains are classified from Grade 1 to Grade 3 based upon the amount of tissue damage, with Grade 1 representing strain without significant fiber tearing, Grade 2 indicating partial muscle tearing, and Grade 3 signifying complete muscle or tendon rupture.

The hamstring muscle is the most commonly strained muscle in the lower extremity of elite athletes (3).Sports that involve sprinting and jumping, like track, football and soccer predispose athletes to strain injuries while participants in water skiing, martial arts and dancing are more prone to stretch-type injuries (1,4,5). Strains related to sprinting or running often occur just before foot contact as the hamstring muscles are stretched and working hardest (6,7).

What are the risk factors for hamstring strains?

The majority of sports related hamstring injuries tend to occur during competition, particularly as the athlete gets fatigued and tired (38).

Hamstring and Quadricep Balance: An imbalance of muscular strength (overactive quadriceps, underactive hamstrings) leads to injury when excessive quadriceps strength overpowers the capacity of the hamstring (8,38).

In addition to muscular fatigue, a combination of several other factors increases the risk of hamstring strain: insufficient warm up, a history of prior injury, and hamstring inflexibility or weakness (1,8,10,11,16,37,38).

Additional known biomechanical risk factors include tight muscles: quadriceps or iliopsoas (hip flexors), poor lumbar stability, and poor running mechanics (13,14,39). Injuries are thought to occur when the number of risk factors reaches a critical threshold.

Who is is more likely to get hamstring strains?

Hamstring injuries are more common with age and affect African Americans more frequently (15,16). A study of college soccer players suggests that hamstring injures are more common in males (17).

What are the symptoms of a hamstring strain?

Most hamstring injuries occur abruptly during activity with a tearing sensation accompanied by significant pain in the back of the thigh. In about 10 percent of cases, symptoms start more gradually (2). Symptoms of hamstring strain vary from a mild ache to debilitating pain, based upon the site and amount of tissue damage. The most common presenting symptoms include pain in the lower buttock and posterior thigh when straightening the leg, particularly while walking or flexing forward.

Do I need X-rays or imaging for a hamstring strain?

The diagnosis of hamstring strain should be based upon an accurate history and physical evaluation. X-rays are generally unnecessary unless there is suspicion of avulsion fracture of the ischial tuberosity or other pathology (16,19). Advanced imaging of the hamstring, including MRI or ultrasound, (with MRI being more sensitive (21)) is reserved for more severe injuries in order to help determine whether surgical intervention will be necessary (22).

Management of Hamstring strains

The management of hamstring injuries is often challenging for both clinicians and patients, as healing is often delayed with persistent symptoms and re- injury rates between 12 and 31% (23,24).

The proximity of the injury to the buttock crease generally correlates with the recovery period, with more proximal injuries requiring longer resting periods (25,26,39). Recurrent injuries often take twice as long to heal as the initial injury. (28) Athletes who do not adequately rehabilitate their injury and return to sport prematurely are at greater risk of re-injury and diminished performance (4,8).

Treatment of Hamstring Strains

The rehabilitation of hamstring injuries can be divided into three phases.

Phase I: Reduce pain and swelling following an injury. Use the RICE protocol (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation). Ice may be applied 15 minutes on, 15 minutes off. The compression bandage can help limit swelling. Pain tolerance dictates return to normal walking, with light range-of-motion exercises. Avoid excess stretching of the hamstrings initially after injury.

Phase II: Phase II begins with a patient can walk without pain and can perform resisted knee bends. Goals of phase II include flexiblity, strength, and function of hamstrings. Athletes should avoid sprinting and slowly increase their running speed up to 50% of their maximum. Stationary cycling or swimming can be utilized. Stretching of the hamstrings can be utilized in this phase, along with hip flexors, quads, and spine muscles. Nordic hamstring eccentric exercises have significant evidence in rehabbing hamstring injuries and minimizing reoccurrence (33,34). Core stability exercises and agility drills have been shown decrease injury rates compared to isolated stretching and strengthening (23,28). Myofascial release techniques (ART, IASTM) can be used judiciously.

Phase III: Phase III begins when a patient can perform a resisted knee bend without pain and can run at 50% speed without pain. Phase III goals include return to activity through specific drills and trunk stability exercises. Patients will gradually increase from jogging to full sprinting. Early return to sport will likely result in a recurrent or more severe problem (8). Proper dynamic warm up and cool down should be taught.

Should I use NSAIDS fora hamstring strain?

There is some controversy regarding the use of NSAIDS for hamstring strains, as some studies suggest that these drugs may have a negative effect on recovery (30,31 )

At Creekside Chiropractic & Performance Center, we are highly trained to treat hamstring strains. We are the only inter-disciplinary clinic providing services to Sheboygan, Sheboygan Falls, Plymouth, and Oostburg including chiropractic, manual therapy, myofascial release, ART (Active Release Technique), massage therapy, acupuncture, physiotherapy, rehabilitative exercise, nutritional counseling, personal training, and golf performance training under one roof. Utilizing these different services, we can help patients and clients reach the best outcomes and the best versions of themselves. Voted Best Chiropractor in Sheboygan by the Sheboygan Press.

Evidence Based-Patient Centered-Outcome Focused

Sources:

1. Garrett WE Jr. Muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med 1996;24(6 suppl):S2–8.

2. Verall GM, Slavotinek J,Barnes P. Diagnostic and prognostic value of clinical findings in 83 athletes with posterior thigh injury: comparison of clinical findings with magnetic resonance imaging documentation of hamstring muscle strain. Am J Sports Medicine, Nov 2003:31;6 p969

3. Lieberman GM,Harwin SF: Pelvis, hip and thigh,:Sportsmedicine: principles of primary care. Mosby, 1997 pp 306-314h

4. Ekstrand J, Gillquist J. Soccer injuries and their mechanisms: a prospective study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1983;15:267–70.

5. Sallay PI, Friedman RL, Coogan PG, et al. Hamstring muscle injuries among water skiers. Functional outcome and prevention. Am J Sports Med 1996;24:130–6.

6. Garrett WE., Jr Muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:S2–8

7. Orchard J. Biomechanics of muscle strain injury. New Zealand J Sports Med. 2002;30:92–98.

8. Drezner JA. Practical management: hamstring muscle injuries. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:48–52.

10. Worrell TW. Factors associated with hamstring injuries: an approach to treatment and preventative measures. Sports Med 1994;17:338–45.

11. Croisier J-L. Factors associated with recurrent hamstring injuries. Sports Med 2004;34:681–95.

13. Cameron ML, Adams RD, Maher CG, Misson D. Effect of the HamSprint Drills training programme on lower limb neuromuscular control in Australian football players. J Sci Med Sport. 2007;12:24–30

14. Gabbe BJ, Bennell KL, Finch CF, Wajswelner H, Orchard JW. Predictors of hamstring injury at the elite level of Australian football. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16:7–13.

15. Freckelton G, Cook J, Pizzari T. The predictive validity of a single leg bridge test for hamstring injuries in Australian Rules Football Players. British Journal of Sports Medicine. August 2013

16. Woods C, Hawkins RD, Maltby S, et al. The football association medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football: analysis of hamstring injuries. Br J Sports Med 2004;38:36–41.

17. Cross K, Gurka K, Saliba S, Conaway M, Hertel J. Comparison of Hamstring Strain Injury Rates Between Male and Female Intercollegiate Soccer Athletes Am J Sports Med April 2013 vol. 41 no. 4

19. Clanton TO, Coupe KJ. Hamstring strains in athletes: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:237–248.

21. Kerkhoffs G, et al Diagnosis and Prognosis of Acute Hamstring Injuries in Athletes. Knee Surg Traumatology Arthrosc. 2013 February; 21(2): 500-509

22. Koulouris G, Connell D. Hamstring muscle complex: an imaging review. Radiographics. 2005;25:571–586.

23. Sherry MA, Best TM. A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2004;34:116–25.

24. Heiser TM, Weber J, Sullivan G, et al. Prophylaxis and management of hamstring muscle injuries intercollegiate football players. Am J Sports Med 1984;12:368–70.

25. Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during slow-speed stretching: clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and recovery characteristics. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1716 26. Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high-speed running: a longitudinal study including clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:197-206.

28. Koulouris G, Connell DA, Brukner P, Schneider-Kolsky M. Magnetic resonance imaging parameters for assessing risk of recurrent hamstring injuries in elite athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1500–1506.

30. Mishra DK, Friden J, Schmitz MC, Lieber RL. Anti-inflammatory medication after muscle injury. A treatment resulting in short-term improvement but subsequent loss of muscle function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1510–1519.

31. Baoge L, Vanden Steen S, Rimbaut N, Philips E, et al. Treatment of skeletal muscle injury: a review. ISRN Orthopedics. 2012

32. Kujala U, Orava S, Jarvinen M Hamstring Injuries. Sports Medicine June 1997, Volume 23, Issue 6, pp 397-404

33. Hawkins RD, Hulse MA, Wilkinson C, Hodson A, Gibson M. The association football medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:43–47 3

4. Copeland ST, Tipton JS, Fields KB. Evidence-based treatment of hamstring tears. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009 Nov-Dec;8(6):308-14.

37. Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Barnes PG, et al. Clinical risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury: a prospective study with correlation of injury by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:435–9.

38. J Petersen, P Ho ̈lmich. Evidence based prevention of hamstring injuries in sport Br J Sports Med 2005;39:319–323

39. Bryan C. Heiderscheit, BC et al. Hamstring Strain Injuries: Recommendations for Diagnosis, Rehabilitation and Injury Prevention JOSPT 2010 February; 40(2): 67-81

40. Greenstein JS, Bishop BN et al. The Effects Of A Closed-chain, Eccentric Training Program On Hamstring Injuries Of A Professional Football Cheerleading Team J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2011;34:195-200