What is IT Band Syndrome?

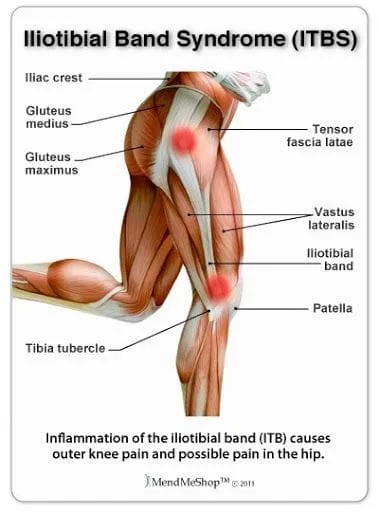

Iliotibial Band syndrome, or "IT Band Syndrome" is caused by irritation of the tissues near the attachment of the iliotibial band. This overuse syndrome is particularly common in runners and cyclists.

What is the IT Band?

The ITB is part tendon, part ligament and runs the length from the lateral hip to knee. It is divided anatomically into two distinct portions- a “tendinous” segment and a “ligamentous” component (4). The It band starts as a sheath that wraps around the TFL muscle. This anchors the TFL to the pelvis and also gets most of the gluteus maximus tendon. The IT band also has a deeper component that is attached to the shaft of the femur. The IT band turns into a ligamentous-type structure near the knee, and is attached to the outside of the tibia. The portion of the IT band just above the knee is protected from rubbing against the bone with a highly sensitive fat pad. This is relatively new research, as many had previously thought that there was a bursa in this area (4).

What causes IT Band syndrome?

Current explanations for the cause of ITB syndrome focus on compression of a highly innervated fat pad between the ITB and epicondyle that is compressed when the band is taut (4,8).

Earlier theories (7) suggesting that ITB syndrome is a “friction syndrome” resulting in irritation, however – there is no bursa and the band does not undergo friction inducing movement.

Who is most likely to get ITB Syndrome?

ITB syndrome is common in with people who perform repetitive knee banding and straightening while on one leg (9) The problem is particularly prevalent in runners, where it compromises almost 1⁄4 of all lower extremity injuries (2,3,10-17). Ultimately, ITB syndrome affects up to 12% of all runners (10). The condition is also frequently seen in cycling, weight lifting, skiing, soccer, basketball, field hockey, and competitive rowing (16,18-20).

What are the risk factors for ITB Syndrome?

Risk factors for the development of ITB syndrome include TFL hypertonicity, high mileage running, running on a circular track, and weakness of the knee extensors, flexors, or hip abductors (1,22). Weak hip abductors internal stress on the thigh and internal rotation of the knee during movement. This leads to increased tension on the ITB with a predisposition for a compressive irritation of the tissues underneath (8).

Do fallen arches, flat feet, or hyperpronation affect ITB Syndrome?

Unlike most lower chain problems, foot hyperpronation does not seem to be a problem – in fact, research suggests ITB syndrome is more likely in populations with high arches (23)

What are the symptoms of IT Band Syndrome?

The typical presentation for ITB syndrome is a runner or cyclist complaining of “sharp” or “burning” pain just above the lateral knee (9). Pain may radiate higher or lower (9). Symptoms are provoked by activities that require repetitive knee flexion and extension. Symptoms are more likely as activities proceed (9). Less severe presentations may report pain only during activity, but as the condition progresses, symptoms become more constant.

Do I need X-rays or imaging for IT Band syndrome?

X-ray imaging is generally not required or beneficial for the diagnosis of iliotibial band syndrome. MRI may be useful to rule out alternate diagnoses, or in patients who do not respond to a trial of conservative care. (29) Ultrasonography may be an alternate means of imaging the iliotibial band. (29)

How long does IT Band syndrome usually last?

Forty-four percent of patients treated conservatively report complete resolution at two months and 92% report resolution at six months (31).

What are the best treatment options for IT Band syndrome?

Conservative management includes: modalities, activity modification, stretching and hip abductor strengthening (31-34).

Perhaps the single most important aspect of treatment includes strengthening the hip abductors and external rotators (32) The majority of patients who incorporate hip abductor strengthening into their ITB rehab will have symptoms resolve within six weeks (32,33).

IASTM over the band, particularly the distal component, may provide additional benefit. Identification and resolution of joint restrictions is appropriate for the lumbar, sacroiliac, and lower extremity.

What other treatment options are available?

Anti-inflammatory modalities and ice may help to relieve acute inflammation. The use of pharmaceutical anti-inflammatories, including NSAIDs or corticosteroids may provide symptomatic relief for ITB syndrome patients (34).

Treatment of cases that do not respond conservatively may include corticosteroid injections, which have demonstrated benefit in treating ITB syndrome (37).

Does the IT Band need to stretch?

Kind of, but not where you would normally think or feel the pain. The dense fibrous iliotibial band is extremely resistant to stretch (less than 0.2% with maximum voluntary contraction), so flexibility gains must come from the tensor fascia lata and gluteal muscles at the hip (38). Incorporating deep tissue massage or myofascial release prior to stretching may enhance flexibility gains (39-41).

The use of foam rollers or massage sticks may help promote flexibility and decrease stiffness throughout the iliotibial band (6).

Can I still run with IT Band syndrome?

Activity modification may require lower duration of exercise but not necessarily pace. Fast-paced running is less likely to aggravate ITB problems when compared to slower “jogging’ (33).

Patients should begin slowly and increase their distance by no more than 10% per week.

Runners should minimize downhill running and avoid running on a banked surface like the crown of a road or indoor track.

If track work is unavoidable, runners should reverse directions each mile.

Athletes should avoid running on wet or icy surfaces as these require greater TFL activation for stabilization.

Runners must avoid “crossover” gaits, or running with both feet touching the road line, which have been shown to aggravate iliotibial band problems.

Athletes should consider new training shoes, particularly if the current shoes have in excess of 300 miles or show signs of wear on the lateral heel.

At Creekside Chiropractic & Performance Center, we are highly trained to treat this condition. We are the only inter-disciplinary clinic providing services to Sheboygan, Sheboygan Falls, Plymouth, and Oostburg including chiropractic, manual therapy, myofascial release, ART (Active Release Technique), massage therapy, acupuncture, physiotherapy, rehabilitative exercise, nutritional counseling, personal training, and golf performance training under one roof. Utilizing these different services, we can help patients and clients reach the best outcomes and the best versions of themselves. Voted Best Chiropractor in Sheboygan by the Sheboygan Press.

Evidence Based-Patient Centered-Outcome Focused

Sources:

1. S. P. Messier, D. G. Edwards, D. F. Martin et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 951–960, 1995.

2. Ellis R, Hing W, Reid D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome--a systematic review. Man Ther. Aug 2007;12(3):200-8.

3. Hamill J, Miller R, Noehren B, Davis I. A prospective study of iliotibial band strain in runners. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). Jun 24 2008

4. Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, et al. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. J Anat, 2006;208:309-316.

5. Standring S. Gray's Anatomy: the Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 39. Edinburgh: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

6. Michaud T. The Real Cause of Iliotibial Band Syndrome Dynamic Chiropractic November 18, 2012, Vol. 30, Issue 24 Fetto J, Leali A, Moroz A Evolution of the Koch model of the biomechanics of the hip: clinical perspective. J Orthop Sci. 2002; 7(6):724-30.

7. Drogset JO, Rossvoll I, Grøntvedt T Surgical treatment of iliotibial band friction syndrome. A retrospective study of 45 patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999 Oct; 9(5):296-8.

8. Fetto J, Leali A, Moroz A Evolution of the Koch model of the biomechanics of the hip: clinical perspective. J Orthop Sci. 2002; 7(6):724-30.

9. M. Fredericson and A. Weir, “Practical management of iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 261–268, 2006

10. Linenger JMCC. Is iliotibial band syndrome overlooked? Phys Sports Med. 1992;20:98–108.

11. Orava S. Iliotibial tract friction syndrome in athletes-an uncommon exertion syndrome on the lateral side of the knee. Br J Sports Med. 1978;12:69–73.

12. McNicol K, Taunton J, Clement D. Iliotibial tract friction syndrome in athletes. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1981;6(2):76–80.

13. Messier SP, Edwards DG, Martin DF, Lowery RB, Cannon DW, James MK, et al. Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:951–960.

14. Fredericson M, Cookingham CL, Chaudhari AM, et al. Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10:169–175.

15. Taunton J, Ryan M, Clement D, McKenzie D, Lloyd-Smith D, Zumbo B. A retrospective case–control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(2):95–101.

16. Orchard JW, Fricker PA, Abud AT, Mason BR. Biomechanics of iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:375–379.

17. Fredericson M, Wolf C. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: innovations in treatment. Sports Med, 2005;35:451-459.

18. Holmes JC, Pruitt AL, Whalen NJ. Iliotibial band syndrome in cyclists. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(3):419–424.

19. Devan MR, Pescatello LS, Faghri P, Anderson J. A prospective study of overuse knee injuries among female athletes with muscle imbalances and structural abnormalities. J Athl Train. 2004;39(3):263–267.

20. Rumball JS, Lebrun CM, DiCiacca SR, Orlando K. Rowing injuries. Sports Med. 2005;35(6):537–555.

22. M. Fredericson, C. L. Cookingham, A. M. Chaudhari, B. C. Dowdell, N. Oestreicher, and S. A. Sahrmann, “Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 169–175, 2000

23. Ferber R, Noehren B, Hamill J, et al. Competitive female runners with a history of iliotibial band syndrome demonstrate atypical hip and knee kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2010;40:52.

24. Strauss EJ, Kim S, Calcei JG, Park D. Iliotibial band syndrome: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:728–736.

25. Lavine R. Iliotibial band friction syndrome. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2010;3:18–22.

26. Fredericson M, Wolf C. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: innovations in treatment. Sports Med. 2005;35:451–459

27. MacMahon JM, Chaudhari AM, Andriacchi TP. Biomechanical injury predictors for marathon runners: striding towards iliotibial band syndrome injury prevention. Conference of the International Society of Biomechanics in Sports, Hong Kong; June 2000.

28. Noehren B, Davis I, Hamill J. Prospective study of the biomechanical factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin Biomech.

2007;22:951–956. 29. Ellis R, Hing W, Reid D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome--a systematic review. Man Ther. 2007;12:200–208.

30. Strauss EJ, Kim S, Calcei JG, Park D. Iliotibial band syndrome: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:728–736.

31. Beals C, Flanigan D. A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population Journal of Sports MedicineVolume 2013

32. Fredericson M, Cookingham C, Chaudhari A, et al.. Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin J Sport Med, 2000;10:169-175.

33. Fredericson M, Wolf C. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: innovations in treatment. Sports Med. 2005;35(5):451-9.

34. Ellis R, Hing W, Reid D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome—a systematic review. Man Therapy. 2007;12:200–208.

35. Almekinders L. An in vitro investigation into the effects of repetitive motion and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication on human tendon fibroblasts. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:119–123.

36. Kulick M. Oral ibuprofen: evaluation of its effect on peritendinous adhesions and the breaking strength of a tenorrhaphy. J Hand Surg. 1986;11A:110–119.

37. Gunter P, Schwellnus MP. Local corticosteroid injection in iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:269–272

38. Falvey E, Clark R, Franklyn-Miller A, et al. Iliotibial band syndrome: an examination of the evidence behind a number of treatment options. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 2010;20:580-587

39. Hopper D, Deacon S, Das S, et al. Dynamic soft tissue mobilization increases hamstring flexibility in healthy male subjects. Br J Sports Med, 2005;39:594-598.

40. Guler-Uysl F, Kozanoglu E. Comparison of the early response to two methods of rehabilitation for adhesive capsulitis. Swiss Med Wkly, 2004;134:363-368.

41. Chang A, Hayes K, et al. Hip abduction moments and protection against medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis progression. Arth Rheum, 2005;52:3515-3519.

42. Natalie Sidorkewicz, Edward D.J. Cambridge, Stuart M. McGill Examining the effects of altering hip orientation on gluteus medius and mtensor fascae latae interplay during common non-weight-bearing hip rehabilitation exercises. Clinical Biomechanics 29 (2014) 971–976